|

The Czolgosz Case

Undoubtedly measured by the standard

of public decency the spectacle furnished by the Czolgosz trial

contrasts most favorably with those offered by the legal and quasi-legal

procedures ensuing after the murders of Lincoln and Garfield. It

remains a question, however, whether under other circumstances some

of its features would not have to be regarded as—to say the least—inadequate

to the cause of ideal justice. Gross violations of the prisoner’s

legal rights, such as through ignorance of law, natural in a court

composed as that which tried the real and suspected assassins of

Lincoln and several members of his cabinet, was composed, namely

of military men, were avoided. Nor was there evident on the part

of the prosecution any such vindictive spirit as was shown in the

trial of the assassin of our second martyr President, which notoriously

went the length of mutilating exhibits by removing from a prisoner’s

letters such portions as might have suggested or supported the theory

of mental disease. The crime of Czolgosz was so evident, its elements

so repulsive, and its deliberation in its association with anarchist

views so manifest, that a perfunctory prosecution would have sufficed

to secure a verdict entailing the extreme penalty of the law. It

will all the more redound to the credit of the district attorney,

that in favorable contrast with like officers, under like circumstances,

he had the prisoner examined in regard to his mental state without

“instructions to find for the prosecution,” and so examined prior

to having the prisoner indicted. He would, in case of a finding

of evident insanity, have been in a position to evade responsibility

for such a farce as the Guiteau trial constituted.

The prisoner’s attitude rendered the

position of the court an awkward one, and it evidently felt this

keenly. Czolgosz’s refusal to plead, or even to reply to ordinary

questions, made the position of his counsel an even more difficult

one. The latter was under the circumstances limited to one possible

line of defence, that of insanity involving irresponsibility. How

to establish such, nay, how to justify the mere surmise, where the

subject of inquiry wilfully [sic] closes the only channel

by which thoughts and reasoning are exhibited to the examiner, is

a problem rarely presented to the alienist, and when presented,

one of the most difficult to solve. Obstinate mutism has therefore

proven one of the more successful measures of the simulator. It

could, however, prove of no value in the present case as sustaining

the insanity plea, owing to the crass inconsistency of mutism with

the mental state at the time of the shooting. It hence proved but

an additional stumbling block to any defence whatever. That the

prisoner’s assigned counsel felt himself reduced to a purely formal

defence need not surprise one. And when the physicians, who at his

own request, examined this imposed client, reported the latter to

be not insane, the last prop of a material defence fell away and

the counsel cannot be accused of dereliction of duty on the above

ground.

In regard to his closing address,

however, I find a most objectionable feature. It was not necessary

for the counsel to anticipate the prosecuting attorney by calling

up the emotions of the jury on behalf of the martyr victim of his

client. The district attorney scarcely went so far as the defendant’s

counsel in this respect. The pathetic recital of President McKinley’s

noble qualities, the loss the country sustained, the bereaval the

counsel asserted himself to have personally suffered, were all made

truthfully. But we question whether such appeals would have been

regarded as essential to his securing a verdict of guilty by the

public prosecutor. All the less were they in place in counsel’s

final address to the jury in whose hands the fate of his client

was shortly to be placed.

The crocodile tears, which certain

notorious pettifoggers of criminal courts are so apt at calling

forth when required, are regarded justly with equal detestation

and contempt. How shall the tears of genuine grief shed by Czolgosz’s

counsel as he mentioned the bereavement inflicted by his client,

be judged? From the general standpoint of humanity they may be condoned,

but from the strictly professional standpoint the pathos manifested

on so unusual an occasion and in a way so contrary to a client’s

interest does not seem to be in harmony with the dignity, gravity

and propriety otherwise marking the proceedings.

Regarding a point which was and is

of far greater importance than the retributive punishment of the

single assassin, I believe that our police and legal machinery has

proven grievously inadequate. I refer to the existence of possible

accessories, since to my mind there are features in the crime which

point to their existence. The subterfuge of the bandaged hand1

strikingly suggests a female source; at all events the prisoner

does not exhibit the appearance of intelligent spontaneity this

dastardly trick presumes. His itinerarium of the four months preceding

the murder brought him in collusion with persons notoriously associated

with an international set of anarchists. Barely a year ago this

very set was affiliated with the notorious anarchist’s leader, Malatesta,

and about the time of his visit as well as shortly thereafter there

were several warnings, anonymous and otherwise of a plan aiming

at the leading crowned heads. Two of these warnings mentioned the

President of the United States as included in the list of intended

victims. The warnings were too nearly simultaneous and preceded

from too widely separate quarters, South America, the States and

Europe, to have been fortuitously coincident practical jokes. The

event has proven the reality of such a plot; no doubt some of the

selected soloists experienced stage fright at the critical moment,

and not all defalcators could be substituted with as prompt effectiveness

as was Sperandio by Bresci, but within a few weeks of Czolgosz’s

deed, we have Pietrucci’s suicidal attempt revealing prematurely

the mission of Romalino; we have further the suicide of de Burgal

and [693][694] the arrest of several

bearers of related missions at Hamburg, in Buenos Ayres, and at

St. Petersburg.

The method of arresting suspected

accessories of Czolgosz, followed by the police authorities of several

of our cities, smacks of the same panicky stupidity that induced

the authorities to grant a paranoic in the President’s native city

a guard of soldiers to protect him against the phantoms of persecutional

delirium. It was at random and so stupidly initiated and carried

out, that instead of furthering the interest of justice, it simply

furnished opportunity for damage suits on the part of the parties

arrested—which these last are too wise to avail themselves of.

To closet such persons in jail together

with full opportunities for reading the daily papers and seeing

emissaries passing and repassing from one to the other, as was done

in several instances in connection with this case, were worthy of

the palmiest days of Abdera. Solitude, time and uncertain expectancy

are motive springs for confession and betrayal of associates, whose

employment has at all times been regarded as essential to the end

of justice in case of dangers menacing the safety of the State.

But to not one of these has recourse been had and the authorities

lost prestige with the public, and the awe of the guilty by this

random and inconsistent procedure.

It so happens that for what may be

good reasons the prosecution failed to avail itself of a means calculated

to effectively trace and punish accessories, if Czolgosz had such.

Though an unconstitutional law the Conspiracy Law of the State of

Illinois rendered that State the more eligible one to conduct the

trial of Czolgosz in.

In the first place, it provides for

the case of criminals guilty of crimes in other States and extraditable

from such States to its own custody when the crime committed in

the latter is suspected to be the result of a conspiracy in the

State of Illinois. In the second place, the collected facts point

to the location of the presumptive conspiracy in that State. In

the third place, the loopholes in the law open in other States for

a defence of quibbles are closed in Illinois. No matter how objectionable

in principle the legislation securing, and how servile the motives

of the judicial advisor suggesting (at the time of the Haymarket

bomb-throwing) them, these features are advantages the prosecution

would have been justified in availing itself of; what may seem to

justify its neglect to do so is at once a curious and a humiliating

fact.

A prominent police official in Chicago

has with apparent good reason become the subject of investigations

whose ultimate result promises to become a prosecution of a more

serious character. No better opportunity to rehabilitate himself

could have happened than the discovery of criminals so vengefully

regarded by the public as conspirators against our Executive. Accordingly

he was all activity. His opponents fearing the overshadowing of

their energy by a successful coup, did everything in their

power to throw discredit on his efforts, and the old proverb about

honest men coming to their own was illustrated in an inversion:

when the authorities fall out, the guilty escape.

As to the mental calibre of Czolgosz,

generally speaking, I recognize nothing particularly differentiating

it from the average persons belonging to his class, or if you please,

“party.” There is the same contracted view of the individual’s relations

to his surroundings; the same false ideal of heroism, and, what

must not be lost sight of, the same obstinate loyalty to his associates,

a feeling which will probably conduct him through the ordeal of

punishment without revealing their identity and share in the crime.

Like most anarchists2 he has not acquired

any skilled trade, nor has he, in fact, shown any capacity in other

directions than the coarsest kind of manual labor. I believe that

the scene which has been related in the press as his “collapse on

arriving in jail” may bear a different interpretation. His movements

are described as an unloosening of all his limbs in jactatory movements.

They occurred when the attendants seized him to put the prison garments,

which are of a somber hue, on him. Czolgosz imperfectly comprehending

his sentence, whose terms it must be remembered, are in this State

indefinite as to the precise time of execution, may have apprehended

that this sentence was being carried out instanter, and his conception

of the influence of the lethal current by “suggestion” as it were,

was illustrated in the movements which struck casual observers as

so singular.

In a study made some years ago relative

to mental epidemics and historical periods as influencing insane

mentality as well as its sane counterpart, it appeared incidentally

that assassinations have not become more frequent in the present

era. The social disease of which these acts are mere surface manifestations

has been coeval with the history of civilization, and under different

guises has produced corresponding results at all times.

From the cuneiform inscriptions to

the modern book page, the records of assassination are distributed

with the same surprising evenness as are the analogous ones of suicides

and of epidemic insanity. That assassination has ceased to be a

relaxation of the opulent and ruling classes as it was in the days

of the Ptolomies, Seleucides, Perseus and Jugurtha, and occasionally

also in the later days of the Plantanegets and the Borgias, is paralleled

in other fields. In those days it required a strong provocation

of the ego to nerve a proletarian against a governor or a king,

as it did a slave to avenge a beloved master by slaying Hasdrubal,

and the peasant stab the repacious [sic] tax collector L.

Piso. Later religion supplied the motive, and from the fanatics

who poinarded the chiefs of Kufa down to the Ravaillacs, Gerards,

Clements and Damiens, its strong influences were felt. Still later

these gave way with the developing prominence of economical and

social questions to socialistic, atheistic, libertinistic and chaotic

views generally. That they contained devotees in their ranks such

educated men as was for example the assassin, Nobiling, is [694][695]

among the incomprehensible features of the subject. Equally is the

fact that any historical student, for such he was, could ever have

dreamed of any good result accruing from assassination. A summary

of the facts elicitable from the figures in the sequel might be

made the basis of an educational chart for the use of anarchists

and other terrorists.

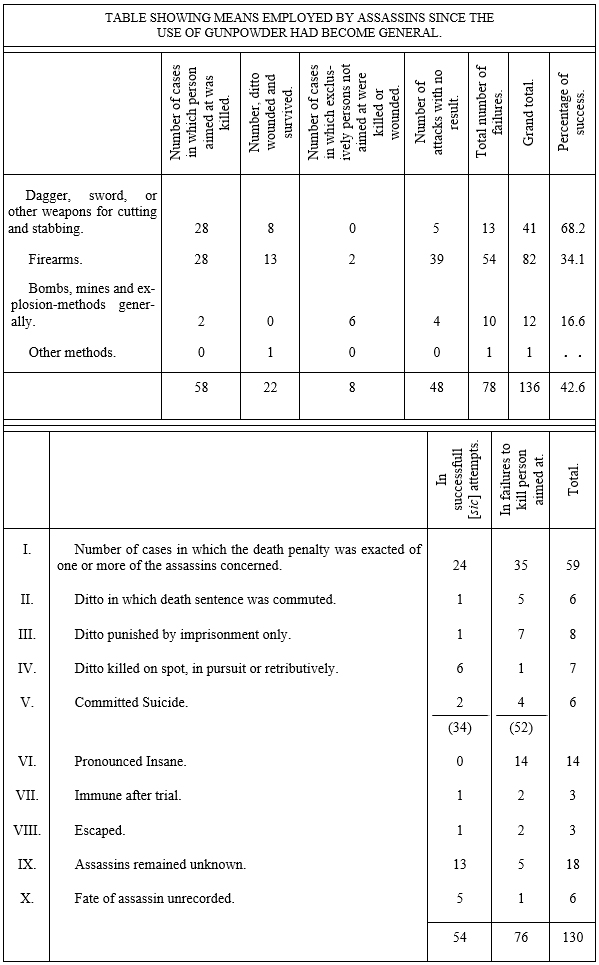

Of 588 murders attempted and consumated

[sic], including all instances in which those prominent in

history have been killed from political, dynastic or other reasons

connected with the public station of the victim, 277 may be termed

assassinations in the accepted narrow meaning of the word, equivalent

to the attentat of continental writers. Of these, 155 succeeded

in so far as the death of the victim ensued. Of these, 52 were avenged

by the legal execution of one or more of the perpetrators, 20 by

instant death at the hands of guards or the public by the killing

of the flying assassin or by his suicide; a total of 75 cases in

which death was retributive. In 5 additional cases execution occurred

for later crimes, the perperator [sic] having escaped the

immediate consequences of the former, and in 3 further cases suicide

similarly ended the criminal’s career. In 61 cases execution, in

6 suicide, and in 3 retributive assassination avenged unsuccessful

attempts.

The “mortality” by legal and other

retributative [sic] measures was therefore over fifty-five

per cent. Excluding those cases where the deed was done under protecting

influences, as were Czolgosz’s and Masamiello’s for example, over

eighty per cent. of the assassins perished.

|

![]()