| Publication information |

|

Source: National Magazine Source type: magazine Document type: editorial column Document title: “Affairs at Washington” Author(s): Chapple, Joe Mitchell Date of publication: October 1901 Volume number: 15 Issue number: 1 Pagination: 5-30 |

| Citation |

| Chapple, Joe Mitchell. “Affairs at Washington.” National Magazine Oct. 1901 v15n1: pp. 5-30. |

| Transcription |

| full text |

| Keywords |

| White House; William McKinley (death: personal response); William McKinley (personal character); William McKinley (at Pan-American Exposition); Pan-American Exposition (President’s Day); McKinley assassination; William McKinley (death); William McKinley (death: persons present in Milburn residence); William McKinley (death: public response); William McKinley (mourning); Louis E. McComas (public statements); William McKinley (death: public response: Canton, OH); Theodore Roosevelt (assumption of presidency); Theodore Roosevelt (swearing in: persons present in Wilcox residence); Theodore Roosevelt (swearing in); Theodore Roosevelt (public statements); Theodore Roosevelt (first official proclamation: full text); Theodore Roosevelt (fitness for office); presidents; Arthur Brisbane (public statements); Charles H. Taylor (public statements). |

| Named persons |

| John Adams; John Quincy Adams; Frederic Archer [first name misspelled below]; Chester A. Arthur; John Barber (McKinley nephew); Mary Barber (Ida McKinley niece); Theodore Alfred Bingham; Arthur Brisbane; Wilbur C. Brown [identified as William below]; James Buchanan; Julius Caesar; Charles Cary [misspelled below]; Grover Cleveland; George B. Cortelyou; Leon Czolgosz [misspelled below]; Charles G. Dawes; Chauncey M. Depew; Sarah Duncan (McKinley niece) [first name misspelled below]; Sarah Elizabeth Duncan (McKinley sister) [first name misspelled below]; William McKinley Duncan; Robert Lee Dunn; Ralph Waldo Emerson; Millard Fillmore; James A. Garfield; Ulysses S. Grant; Marcus Hanna; Benjamin Harrison; William Henry Harrison; Rutherford B. Hayes; Webb C. Hayes; John R. Hazel; Ethan A. Hitchcock; Andrew Jackson; William Martin Jeffers [identified as Jeffords below]; Thomas Jefferson; Andrew Johnson; Abraham Lincoln; Henry Cabot Lodge; William Loeb; Charles Loeffler; John D. Long; James Madison; Matthew D. Mann; Charles McBurney [identified as Burney below]; Louis E. McComas; Abner McKinley; Helen McKinley; Ida McKinley; James F. McKinley (nephew); Katie McKinley [in notes]; William McKinley; John G. Milburn [identified once as James below]; James Monroe; Herman Mynter; Francis M. Osborne; Roswell Park; Franklin Pierce (a); Thomas Collier Platt; James K. Polk; Presley M. Rixey; Theodore Roosevelt; Elihu Root; Charles Emory Smith; John Philip Sousa; Charles G. Stockton; Charles H. Taylor; Zachary Taylor; John Tyler; Martin Van Buren; Eugene Wasdin; George Washington; Ansley Wilcox [first name misspelled twice below]; James Wilson. |

| Notes |

|

“Affairs at Washington” is a regular feature of this magazine, serving

normally as an editorial column.

No text appears on pages 11, 15, 19, 21, 23, and 27-29 of this article.

This article includes photographs captioned as follows: President McKinley’s

Second Child Katie, Who Died at the Age of Three and One-Half Years (p.

5); The Home of John G. Milburn, Where President McKinley Died (p. 6);

Library in the Home of Ainsley Wilcox of Buffalo, Where Theodore Roosevelt

Took the Oath of Office as President (p. 7); President and Mrs. McKinley

Leaving the Train at Niagara Falls (p. 8); President McKinley Delivering

His Address in the Esplanade Near Triumphal Bridge, Sept. 5 (p. 9); President

McKinley Reviewing the Troops in the Stadium on President’s Day (p. 11);

Secretaries Gage, Hitchcock and Root and Attorney-General Knox, a Snapshot

Taken at Buffalo (p. 12); President McKinley and John G. Milburn Leaving

the New England Building, President’s Day (p. 13); Veterans of the Spanish-American

War in the Funeral Procession at Washington (p. 15); President McKinley

Being Carried into the Emergency Hospital Just After the Shooting (p.

16); President McKinley and Mr. Milburn in a Carriage at Niagara Falls

(p. 17); Pan-American Emergency Hospital Nurses, President McKinley’s

Attendants (p. 19); President, Then Vice-President, Roosevelt Met by Interviewers

on Leaving the Milburn Home the Last Sunday of President McKinley’s Life

(p. 21); Removal of the Casket from the Hearse into the Capitol Rotunda

(p. 23); Dr. Rixey, the President’s Physician (p. 25); Mr. and Mrs. McKinley

Leaving the Train at Buffalo (p. 25); President McKinley’s Simple Baggage

Being Taken from the White House to the Depot (p. 26); President McKinley,

Secretary Wilson and John G. Milburn at Niagara Falls (p. 27); Theodore

Roosevelt, 25th President of the United States (p. 28); President Theodore

Roosevelt at His Desk (p. 29); President McKinley’s Carriage in the Funeral

Procession (p. 30).

Image courtesy of Google Books. |

| Document |

Affairs at Washington

WHEN I stood in the President’s office at the White House during the now buoyant,

now breathless moments of the last days of our late beloved President, what

a flood of memories came upon me. The canvas-covered furniture, the cool, white

matting, that has replaced the heavy carpets, the world atlas lying closed on

the desk, the deathly silence and quiet only broken by the ceaseless ticking

of the sounders in the “war telegraph” room—tears came to our eyes as we looked

for the cheery, genial face to complete the picture; and yet the bulletins at

that time were radiant with hope for recovery. There was the yellow-arm, revolving

chair at the head of the table in the cabinet room, just down the steps. There

were the ink well, pens and calendar just as he had left them when he departed

for the old home in Canton. Captain Loeffler, the veteran doorkeeper, was still

at his post, and all who entered spoke in whispers of the suffering one. There

was a rustle of newspapers in the secretary’s room, where clippings were being

made for the executive mansion scrap book; adding another chapter to the great

portfolio. Outside, the flowers bloomed with all the mature radiance of autumn.

The White House was being repaired for the comfort

and convenience of the sweet-faced invalid mistress, on plans made during the

happy Maytime. The painters were giving the portico and railing the finishing

touch, and the newly gilded tops of the railing glistened in the September sunlight.

Modest, home-like, unpretentious, there was a touch of the American devotion

to home-making in it all; an expression of the ruling ideal [5][6]

of the man at the head of the nation, who was first and always for the fireside

and the home circle.

——————————

The heartfelt world-tributes to the memory of

William McKinley have no parallel in all history. A reunited country—a world’s

admiration: from every clime and class—every race and nation—come the simple

tributes of affection, which no words can transmit; the subtle, inexpressible

language of the soul.

Readers of “The National Magazine” can realize

with what a heartache the record must be made—President McKinley is dead. In

common with millions the loss comes to this writer with the full force of a

personal bereavement. What a high inspiration for the myriads of the human race

radiated from the gentle, unselfish, great heart, that will never cease to beat

in the spirit of love and helpfulness of humankind!

We look up through blinding tears and listen to

the dying words echoing and re-echoing in human hearts and minds throughout

the world:

“It is God’s way. His will, not ours, be done.”

September 6, 1901, passes into history as a black

and bitter day, lightened only by the sublime courage and calm resignation of

its martyr.

——————————

The personal side of the life of William McKinley

was so perfectly and consistently blended with his public career, that he was

an epoch-making force not alone in practical affairs, but also in the realm

of the spiritual; and his life and career constitute one of the noblest examples

for mankind in history. [6][7]

There is a tremble in the hand and a quiver in

the voice of whomsoever one meets, in these sad days, that tells of the death

of a martyr president. The endeared wife and those who gather about the vacant

chair at the hearthstone; every citizen of the great nation; the entire civilized

world, aye, the human race, measures a loss in the death of the brave, gentle

soul that passed away with such words as indicated the dominating purposes of

his life.

It will require years of historical perspective

to measure the full-statured, heroic and triumphant greatness of William McKinley,

a president perfectly blended with the man as a pure type of Christian manhood;

not only mature and well rounded in itself, but one of those personalities whose

simple strength is a concrete inspiration and influence that will endure in

the lives of millions of American citizens. The close range of vision makes

William McKinley’s life [7][8] and career a more

positive and vitalizing influence upon the young minds of to-day than even Washington

or Lincoln, because William McKinley is not on a pedestal, lent glamor by the

lapse of years, but was only yesterday a living, breathing presence—a force—coming

into personal touch with this time and this people.

——————————

The world echoes with praise of the perfect career of William McKinley. He was shot down while extending that warm, magnetic, helping hand that has done so much for humankind. The bullet was aimed at the heart that always beat in sympathy for the wants of his fellow men and idealized the American fireside. And yet his work was not finished. Such a character was needed to impress upon human minds the highest and noblest ideals of life; he was a willing sacrifice to his country—yes, to the human race, to give the world an ideal sanctified in blood and everlasting love.

——————————

As the President and his wife left that beloved

home in Canton on that bright autumn morning, they both looked back to view

the newly re-painted and re-modeled grey-tinted home, where they had spent so

many happy years; now [8][9] the repairs were completed,

and with all the bright cheerfulness of bride and groom they talked of “our

home.” It was in Canton that the sweetest and tenderest memories of their life

clustered; it was there that their children were born; and there in sunshine

and shadow, in happiness and sorrow, they had typified the ideal and sacred

devotion of husband and wife.

One lingering look—yes, the last happy glance

homeward for that noble home-maker, who as the gallant, beardless soldier had

won his bride, and kept sacred the altar vows by a life’s devotion.

The startling crash of window glass in the Presidential

car followed the welcome announcing the arrival in Buffalo. The presidential

salute had come with the shock of an earthquake; the first thought of the man

in whose honor it was given was for the invalid wife. Tenderly he took her in

his arms and his assurance was enough. With her at his [9][10]

side he was radiant and serenely happy.

“They had more powder than they thought,” he remarked

with a genial smile.

The salutes were fired too close to the car, and

the shattered glass was revealed later as an evil omen of the shattered hopes

of the world, while the people waited for news from the bedside of the beloved

President.

“President’s Day” dawned in the full-orbed splendor

of Autumn. The air was rich with the fragrance of full fruitage. The golden

month was at her best. “It’s McKinley weather” was on every lip as a hundred

thousand people started on their way to the Pan-American Exposition grounds

to see “our President.” Early in the morning the distinguished guests at the

Milburn house on Delaware street were astir. The President carried the copy

of his speech in his inside pocket and stopped during his brief morning walk

about the grounds to jot down a new word or idea.

“I never have overcome the nervousness that comes

over me before making a speech,” he jocularly remarked, adjusting his glasses.

That speech was the ripe thought of the greatest American statesman of the times—and

is one that will live in history. It was the summarizing of an epoch in national

destiny, while the swift-moving events which it recorded were still fresh in

the minds of the people. It was an account of his stewardship to the American

nation, fraught with inspired foresight and fragrant with love and affection

for the people and the highest ideals of patriotism.

——————————

The carriage bore them through the crowds to the Triumphal Bridge and then in the full glory of the September morning, with the gay flutter of flags of all America and the dreamy haze of Indian summer settling over the esplanade and fountains, the people gathered to hear what was destined to be the farewell address of the twenty-fourth president of the United States. There was a hush when he arose to speak, and the deliberation with which he wiped his eye glasses gave him time to overcome the nervousness that confronted him at the opening of every address. Raising his head and looking over his glasses in a kindly way, in full, rounded, measured tones, he delivered an address which was caught up and flashed around the world within a few hours of its utterance. It was an important message to the world and looked to the future. How gentle and significant was the scene; for nowhere have the peaceful achievements of the country been more thoroughly indexed than at the Pan-American. The throng that assembled on that bridge was an interesting study—truly typical of the country.

——————————

Citizens from all the various states and territories brushed elbows there; diplomats from the nations of the world, silk-tiled [sic] and conventional in black Prince Alberts. Orient and Occident were merged in that throng and everyone was thrilled. Thousands stood by patiently until the last words were spoken, although comparatively few in that vast assembly could hear what the speaker said. Little did any one think what precious, golden moments were passing!

——————————

Conspicuous in the crowd assembled on the Esplanade

to hear President McKinley’s speech, were several “National Magazine” badges,

worn by delegates to the “National’s” Pan-American Convention who remained to

greet the President. He sent his regrets at being un- [sic] to attend the “National’s”

convention. Children were everywhere present, and gave vent to wilder enthusiasm

than their elders. A pretty little maiden with fluffy hair demurely stood in

her father’s coat pocket, with her arms tightly clasping his neck, and from

this exalted posi- [10][12] tion she was the first

of her little group to see the President as he drove up.

“See! there he is! mamma, papa, mamma, there he

is! Get up here, mamma; you can see just fine!”

The good natured crowd laughed at the childish

enthusiasm.

“I want to see,” came a pleading voice from a

little boy who was digging his head in the coat tails of a man in front. A second

later he was elevated to the broad shoulders of a six-foot giant and a tired

little woman murmured a word of thanks to the stranger.

“Down with the boy!” shouted a man just behind,

who was short in stature.

“Never!” came back the reply. “You can’t down

the American boy.” And the short man cheered with the rest.

“Mamma, did you see? He wipes his glasses just

like Uncle George. Oh, but he must be a nice man.” “Hush, my child,” said the

father, but the seed had been sown for a new thought in the mind of a grey-haired

man standing near.

“That’s just the way Lincoln used to do. It’s

the same thing over again; our greatest presidents are the humblest.”

——————————

The party was driven to the Stadium. The presence

of carriages on the grounds was a mark of the distinguished occasion. And yet

do you know one of the ambassadors remarked that it was suggestive of a funeral

cortege. The President preferred walking among the people, where it was possible.

Very sturdily he walked into the great Stadium

under a scorching sun, to review the troops. The great, umbrella-bearing throngs

rose to greet the President as he passed, and every [12][13]

outburst of applause was met with that graceful bow and sincere salute which

was distinctly characteristic of William McKinley. It was an expression of patriotic

and personal devotion seldom witnessed. Standing on the reviewing stand I was

thrilled to the finger tips, and somehow the thought flashed over me: Is this

the crest of the wave?

His last review will remain a vivid memory to

the thousands in the arena. As the troops passed with that elastic, swaying

quick step, keeping time to Sousa’s new march, the “Invincible Eagle,” the President’s

face beamed his pleasure and his coat was flying open as if showing the open

hearted honesty of the man; he was somehow a part and parcel of the people,

and it was the people who furnished the pageant for him rather than the troops.

The diplomatic corps, representing all nations, caught the infectious enthusiasm

and one member remarked:

“Such patriotism is an invulnerable bulwark of

national strength.”

As the late President ascended the steps of the

stand, gravely dignified but happy-faced, his deep blue eyes glistened in the

radiant noon-day sun. He graciously bowed to the ladies on the stand.

“Are you fatigued,” inquired a lady standing near

me.

“Oh, no; I’ve had a good six weeks’ rest at home,”

he replied in his cheery way.

As he turned to watch the troops, with the fingers

of one hand he tapped the railing in time with the music, for if any one liked

music it was our late President. Alert, attentive and always interested, he

made every man in line feel that he was receiving personal greeting. And herein

was one secret of the superlative strength of William McKinley; he was always

interested, and his sincerity was never questioned, nor was there ever a partiality.

Always poised for emergencies, never did a shadow of hypocrisy pass over that

kindly face. When he turned and saw my “National Magazine” convention badge

of red, white and blue, he smiled.

“The colors are right”—and then, al- [13][14]

most in the same breath, were scattered those brief words and acts of kindliness

to scores of others which enshrine his memory in affectionate remembrance.

As the party passed out near the court of lilies,

the homing pigeons were brought forth from the dove-cote and long and steadfastly

he gazed at the circling birds, emblematic of the peace he loved. Peace, prosperity

and happy homes were the watchwords of his career, from the time when he first

took an official green bag as county attorney, until the last days of his life.

——————————

That evening, in the gentle twilight of fairyland

glowing on the shore of Mirror lake, with the illuminated buildings and trees

in the background, the President witnessed for the last time the glories of

nocturnal splendor. Happy and cheerful, and as interested as when a barefoot

boy at Niles, Ohio, when the Fourth of July pyrotechnics were in progress, he

enjoyed every flash of the swift, shooting rockets and clusters of light in

the cloud-banked sky. The flickering shadows and the dense darkness among the

trees made some of his personal protectors tremble, but he seemed to have no

consciousness of peril and discussed lightly the plan for the morrow, when he

was to visit Niagara.

Ah, that most touching, last morning! From the

vine-covered verandah he came, with Mrs. McKinley, to greet the splendor of

the new day! With her coat on his arm, (no man was ever more devoted) he turned

to greet even those who held the cameras. The grand old flag he loved made the

background of the picture. Mrs. McKinley was hidden behind a parasol, and even

there was the genial face of the President to say:

“I’ll just have to let you have a picture.”

What a happy day seemed ahead! Appreciative of

every moment the President and members of the cabinet stood upon the banks of

the greatest wonder of the world, and watched the water in its onward rush to

the sea. Thoughtful and considerate of the comfort of his wife and others, he

had never a care for his own pleasure.

——————————

Just three hours before the fatal shot was fired,

the President, for the first time in weeks, requested a picture. Quick as a

flash it was taken by Mr. Dunn of “Leslie’s Weekly,” before the word was scarcely

uttered. Attired simply in a silk hat and black Prince Albert, with a white

vest, from which hung a simple gold fob, and his gloves, he looked every inch

the great man he was.

The President’s watch came out frequently, because

if there was ever a methodical, punctual man, he was, and most anxious that

the thousands at the Temple of Music should not be kept waiting. The train arrived

at the north gate and the party was hurried past the Propylea [sic] and well

into the midst of a sea of humanity, greeting him as he proceeded.

He wore an air of serious purpose, as he pressed

onward, not to disappoint or keep the people waiting. The throng were packed

against the door and had to pass in and out through an improvised aisle lined

on either side with seats. Directly between the two stood the President, with

Secretary Cortelyou on the right and President Milburn on the left. The President

pulled out his watch again to see if he was on time, and looked about admiring

the interior of the temple. Little could I think, as I caught a last glimpse

of that beloved face among the hustling crowd, of the impending tragedy. Here

in the gaieties of dedication day songs and chimes had gone forth; the Vice-President

and Senator Lodge had spoken with Senator Hanna on the platform. Here, during

the summer days, music lovers had gathered at the recitals given at this now

fatal hour of four o’clock every afternoon. Here it was our Frederick Archer’s

magic touch had [14][16] brought forth the heights

and depths of the “Pilgrim Chorus” from “Tannhauser.” Here it was that the very

artistic spirit of the Exposition centred—in fact—the magnet, the meeting point,

the place where the sessions of all of the conventions and all special day exercises

had been held. Here was where romance, comedy, music dwelt—and now deep-dyed

tragedy stalked in.

——————————

The people began to pass forward, shake the President’s

hand and move on. In the twinkling of an eye it occurred. Standing within fifty

feet were hundreds of people who did not know what had taken place. There were

two shots in quick succession, about 4:12 p. m., but nothing was thought of

that because it could easily be confounded with the shooting from Indian festivities

outside. I saw vaguely a scuffle and my thought was, “Some drunken man.” Then,

when the President was taken to the inner side of the stage my first thought

was that he had fainted from the fatigue of the arduous duties of the day. The

people were stunned when the first ghastly whisper came across the room:

“The President is shot!”

Many would not believe it, but a few moments later,

when they carried a limp form out to the ambulance, with the crimson blood staining

the white vest, the awful realization came. Men, women and children burst into

tears, the hard, white lines showed first in a desire to mete out some adequate

punishment to the cowardly assassin.

The frenzy was fearful to contemplate.

“String him up! Kill him!”

Czolgozc—Shawlgotch—the young Polish-descended,

American-born Anarchist, was beaten down by soldiers and the Georgia negro waiter

at the Plaza restaurant, who was in line, and before the dazed crowd had realized

the truth, the officers tried to sooth [sic] them with the report that it was

all a mistake; but very soon all knew that the President was lying in the Pan-American

Emergency Hospital, wounded and near to death.

——————————

The deadly hurts were tended with all the skill

that the President’s own physician, Dr. Rixey, and a group of famous colleagues

could bring to bear, and the distinguished patient was removed to the Milburn

house, where his stricken but brave wife might be near him in any crisis that

might impend.

“This is not our first battle, Ida,” he [16][17]

said to the sobbing woman at his bedside. “We have won more desperate cases

than this. And though conditions may be critical, if there were only one chance

in a thousand I would accept that chance and, for your sake, hope to win.” Then

followed the days of hopeful news from that bedside, when it seemed as if the

indomitable courage of the wounded man would conquer, and he would be spared

to his people. The public fears grew lighter as reassuring bulletins followed

each other twice or thrice daily.

What a wave of grief, almost of anguish, swept

over the land when on Friday morning, September 13, just a week after the shooting,

the correspondents camped in tents across the street from the Milburn home flashed

to all the world the word that the President had had a relapse—that he was very

low, sinking, and that the doctors had all but yielded the last hope. The world

stood still with bated breath, praying, hoping against hope that he might rally

and rise from the dark shadows that encompassed him.

But it was not to be. Recovering consciousness

near the last, the dying man bade his physicians to cease the futile struggle.

“Let me die,” he whispered. He knew that he must go, and with the simple, sublime

courage that marked him on the field of Antietam, he met the inevitable with

calm and unruffled front.

——————————

In this interval of consciousness Mrs. McKinley

was brought into the death chamber. The President had asked to see her. She

came and sat beside him, held his hand, and heard from him his last words of

encouragement and comfort. Then she was led away, and not again during his living

hours did she see him.

The President fully realized that his [17][18]

hour had come and his mind turned to his Maker. He whispered feebly: “Nearer,

My God, to Thee,” the words of the hymn always dear to his heart. Then in faint

accents he murmured:

“Goodbye, all; goodbye. It is God’s way. His will,

not ours, be done.”

With this utterance the President lapsed into

unconsciousness. He had even then entered the valley of the shadow.

Slowly the hours passed without visible change

in his condition, but there was no more hope. There was only the tense waiting

for that moment when the great soul should quit its house of clay. At two o’clock

in the morning of Saturday, September 14, Doctor Rixey was the only physician

in the death chamber. The others were in an adjoining room, while the relatives,

cabinet officers and near friends were gathered in silent groups in the apartments

below. As he watched and waited, Dr. Rixey observed a slight, convulsive tremor

run through the President’s frame. Word was at once taken to the immediate relatives,

who were not present, to hasten for the last look upon the President in life.

They came in groups, the women weeping and the men bowed and sobbing.

——————————

Grouped about the bedside at this final moment

were the only brother of the President, Abner McKinley, and his wife; Miss Helen

McKinley and Mrs. Sara Duncan, sisters of the President; Miss Mary Barber, niece;

Miss Sara Duncan, niece; Lieutenant James F. McKinley, William M. Duncan and

John Barber, nephews; F. M. Osborne, a cousin; Secretary George B. Cortelyou,

Charles G. Dawes, controller of the currency; Colonel Webb C. Hayes and Colonel

William C. Brown.

With these, directly and indirectly connected

with the family, were those others who had kept ceasless [sic] vigil—white-garbed

nurses and the uniformed Marine Hospital attendants. In an adjoining room were

Drs. Charles Burney, Eugene Wasdin, Roswell Park, Charles G. Stockton and Herman

Mynter.

The minutes were now flying, and it was 2:15 a.

m. Silent and motionless, the circle of loving friends stood about the bedside.

Dr. Rixey leaned forward and placed his ear close

to the breast of the expiring President. Then he straightened up and made an

effort to speak.

“The President is dead,” he said.

The President had passed away peacefully, without

the convulsive struggle of death. It was as if he had fallen asleep. As they

gazed on the face of the dead, only the sobs of the mourners broke the silence

of the chamber of death.

——————————

The last honors paid the dead chieftain in Buffalo,

in Washington and in his home city of Canton are still too fresh in the public

mind to require full recital. Let it be recorded, however, that not one of the

many and mighty triumphs of McKinley’s life approached in scope or intensity

his last great triumph won in death. Such an outpouring of love and devotion

was never paid to the memory of any man in all the history of the earth. There

was scarcely a dry eye among the scores of thousands that looked upon the nation’s

dead where he lay in funeral state, at Buffalo, at Washington and at Canton.

In proudest palace and in humblest cot and tenement alike the sorrow of his

people was profound. Men who had fought him hardest in life paid tear-wet tributes

to his goodness, his loyalty to his country and his God. Never a man to evoke

bitterness against himself, in this hour of his passing he compelled, by the

sweetness and purity of his career, the unreserved love of all them that had

opposed him.

The hand that sought to strike him down did but

exalt him. It served but to throw into a stronger light those mag- [18][20]

nificent qualities that made him the best and most universally beloved chief

magistrate that America ever had.

——————————

One incident of the state funeral at Washington was perhaps more beautifully illuminative of the ties between McKinley and his people than any other memory of that sad occasion. At the start of the procession up Pennsylvania avenue, Monday evening, one wavering soprano voice back somewhere in the wilderness of people sang “Nearer My God To Thee,” the notes of which were on the lips of the President as he descended slowly into the valley of the shadow of death. The affecting refrain was caught up by thousands of subdued voices, which carried it up the thoroughfare, keeping pace with the cortege till the hymn burst forth from thousands more who were banked in upon Lafayette square opposite the White House gates, making the heart swell and tears to gush from eyes that watched the progress up the circular drive under the port cochere. No wonder that later on Monday night Senator Louis McComas, of Maryland, standing on the curb near the temporary residence of the new president, remarked: “The sublime faith in which William McKinley died has done more for the Christian religion than a thousand sermons preached in a thousands [sic] pulpits on a thousand Sundays.”

——————————

The funeral train, bearing the remains of the

beloved President from Buffalo to Washington, and from Washington to the loved

home in Canton, awakened an expression of national sentiment that has no comparison.

The unanimous personal sympathy of the people, enduring privation and hardship

in order to offer an individual tribute to the memory of the dead, was not adequately

recognized in the newspaper accounts. The bells tolled, the people watched and

waited in storm and darkness for hours, and all hearts echoed one continuous

refrain of their fallen leader’s favorite hymns—“Nearer, My God, to Thee,” and

“Lead, Kindly Light.” The telegraph wires were laden with eloquent descriptive

stories inspired by the scenes en route to the state funeral at Washington,

from the first trying ordeal at Buffalo, when President Roosevelt and the cabinet

and the endeared friends looked upon the thin, placid face at the Milburn home,

where the first simple services were held.

How fitting that the final tribute to the remains

should be paid at the old home he loved so well; there among the scenes where

the sweetest and tenderest memories of his life clustered. I never expect to

witness again more impressive scenes. The hands of the city clock were stopped

at 2:15, the hour of his death, and through the court house passed thousands

of old friends from surrounding towns to look upon the face of one they loved

until the pale glare of the electric light lit up the mourning draped walls.

A soldier and a sailor of the United States stood at the head and foot of the

casket draped with the flag which had waved so victoriously at the time of his

first nomination for the presidency.

What a contrast with the thrilling scenes of ’96,

when the crowds came to do honor to the living, with huzzas [sic]—now hushed

and silent. The modest little home, which I had visited a few weeks ago, and

the new porch, which had been so proudly pointed out by the President, carried

no semblance of mourning. An additional electric arc light glowed at the side

of the house. The throngs passed noiselessly and with bare heads as the soldier

sentinel paced the lawn, trampled by enthusiastic admirers only a few years

before. The shutters were closed and thousands kept watch on the last night

that this little home contained the mortal remains of the dead President. The

flowers in urn and vase shimmered with the September [20][22]

dew, as if they, too, were experiencing a grief at the loss. Most pathetic was

the sight of the empty willow rocker, where he sat so many times, swaying back

and forth in the pleasant autumn evenings. What a pathos in this home scene,

and what a flood of recollections it awakened!—the summer Sabbath evenings on

the porch when they returned from Washington, and the little girl played on

the violin “Home, Sweet Home” and “Nearer, My God to Thee;” the cheery sight

of the President taking his fair wife to drive, as gallant as a lover; the swinging

walk up and down Market street, to and from a well-ordered and busy law office.

William McKinley came to Canton at the suggestion

of a beloved sister, who taught in the public schools, who was an inspiration

of his life, and who now sleeps in the cemetery where her distinguished brother

rests in peace. Here was the stone church where the young lawyer had taken the

vows which were sanctified by a life’s devotion as a husband. And on another

corner was the church in which he worshipped. In the fourth pew from the front,

No. 10 in the centre aisle, was where he sat and loved to sing in full, round

bass those dear old Methodist hymns which have cheered the souls of countless

millions. Every scene in this busy little city he loved seemed in some way associated

with him. I arrived by way of Massilon; the dusty road was fringed with vehicles

bringing the people. Special trains from all directions poured in until it seemed

as if there could not possibly be room for any more. The telephone and trolley

poles were draped and there was not a house or habitation that was not in mourning.

The floral tributes have probably never been equalled.

From every nation, from almost every organization, came these tributes—expressing

much and eloquent sympathy in the language of heaven. And yet, with all this

expression of a world’s admiration and affection, the love of the old friends

and neighbors was the most impressive after all.

——————————

Vice-President Roosevelt, reassured by the hopeful

bulletins sent out by the President’s physicians during the first week, and

having not the least doubt of the President’s speedy recovery, had gone into

the northern New York woods to hunt.

There the news of his chief’s demise reached him.

As rapidly as special trains could bear him on he rushed to Buffalo, where the

members of the cabinet were assembled. He went at once to the home of his friend,

Ainsley Wilcox, and at 3:39 o’clock on the afternoon of Saturday, September

14, he took the oath of office as President of the United States.

The scene, as witnessed and described by a staff

writer of “The Boston Globe,” was one of the most dramatic and awesome in American

history, and will never be forgotten by the half hundred persons who witnessed

it.

The officials arranged themselves in a semi-circle,

the Vice-President in the centre.

On his right stood Secretaries Long and Hitchcock,

and the Vice-President’s private secretary, William Loeb. Standing on his left

were Secretaries Root, Smith, Wilson and Cortelyou and Senator Depew. About

the room were scattered Ansley Wilcox, James G. Milburn, Doctors Mann and Mynter,

physicians to the late President; Dr. Charles Carey, William Jeffords, official

telegrapher of the United States Senate; Colonel Bingham of Washington, the

newspaper men and several women friends and neighbors of the Wilcox family.

At precisely 3:32 o’clock Secretary Root said

in an almost inaudible voice:

“Mr. Vice President, I—” then his voice broke,

and for fully two minutes the tears ran down his face and his lips [22][24]

quivered so that he could not continue his utterances.

There were sympathetic tears from those about

him, and two great tear drops ran down either cheek of the successor of William

McKinley.

Mr. Root’s chin was on his breast. Suddenly throwing

back his head as if with an effort, he continued in a broken voice:

“I have been requested on behalf of the cabinet

of the late President—at least those who are present in Buffalo, all except

two—to ask that for reasons of weight affecting the affairs of government you

should proceed to take the constitutional oath of office of the President of

the United States.”

——————————

Judge Hazel had stepped to the rear of Mr. Roosevelt,

and the latter coming closer to Secretary Root, said in a voice that at first

wavered, but finally became deep and strong, while as if to control his nervousness

he held firmly the lapel of his coat with his right hand:

“I shall take the oath at once, in accordance

with your requests, and in this hour of deep and terrible national bereavement

I wish to state that it shall be my aim to continue, absolutely unbroken, the

policy of President McKinley, for the peace and prosperity and honor of our

beloved country.”

——————————

Mr. Roosevelt stepped farther into the bay window,

and Judge Hazel, taking up the constitutional oath of office, which had been

prepared on parchment, asked Mr. Roosevelt to raise his right hand and repeat

it after him.

There was a hush like death in the room as the

judge read a few words at a time and the President in a strong voice and without

a tremor and with his raised hand as steady as if carved from marble repeated

it after him.

“And thus I swear,” he ended it. The hand dropped

by his side, the chin for an instant rested on the breast and the silence remained

unbroken for a couple of minutes, as though the new President of the United

States were offering silent prayer.

Judge Hazel broke it, saying: “Mr. President,

please attach your signature.”

And the President, turning to a small table near

by, wrote “Theodore Roosevelt” at the bottom of the document in a firm hand

and at 3:39 o’clock Theodore Roosevelt began his career as President of the

United States at the age of forty-two.

Secretary Root was the first to congratulate him.

The President then passed around the room and shook hands with everybody.

The first act of the new President, his formal

announcement calculated to reassure the industrial interests of the country,

won the confidence of these great interests, and the toilers dependent upon

them, and made it sure that the tragedy which had shocked the world would not

be followed by the depressing effect of administrative uncertainty. The new

President’s first official act was to proclaim the following Thursday, September

19, as a day of mourning and prayer throughout the United States. In this proclamation

he said:

“A terrible bereavement has befallen our people.

The President of the United States has been struck down; a crime committed not

only against the chief magistrate, but against every law-abiding and liberty-loving

citizen.

“President McKinley crowned a life of largest

love for his fellow-men, of most earnest endeavor for their welfare, by a death

of Christian fortitude; and both the way in which he lived his life and the

way in which, in the supreme hour of trial, he met his death, will remain forever

a precious heritage of our people.

“It is meet that we as a nation express our abiding

love and reverence for his [24][25] life, our deep

sorrow for his untimely death.

“Now, therefore, I, Theodore Roosevelt, President

of the United States of America, do appoint Thursday next, September nineteen,

the day in which the body of the dead President will be laid in its last earthly

resting place, as a day of mourning and prayer throughout the United States.

“I earnestly recommend all the people to assemble

on that day in their respective places of divine worship, there to bow down

in submission to the will of Almighty God, and to pay out of full hearts their

homage of love and reverence to the great and good President whose death has

smitten the nation with bitter grief.”

——————————

Theodore Roosevelt, as stated elsewhere, is the youngest man ever called to the presidency of the United States. But he is remarkably well equipped by an unusual training to fulfill the vast and innumerable duties of that position. His career has been an open book to his fellow-citizens for many years past; as author, soldier and public servant he has been always essentially a vigorous, forceful, high-minded man—a natural leader. He aspired to the presidency, and there were very many men high in the councils of his party who regarded him as the logical successor of President McKinley in 1905. Now that the decree of Providence has called him to that succession, the great majority of his fellow-citizens share the conviction expressed by United States Senator Thomas C. Platt of New York, that “he will be a great President.” He has given the clearest evidence of wise statesmanship by pledging all the members of President McKinley’s cabinet to serve out their terms as if there had been no change in the head of the administration. It is conceeded [sic] that Mr. McKinley, with his genius for executive affairs, drew about him one of the ablest and best balanced cabinets that has ever sat in Washington.

——————————

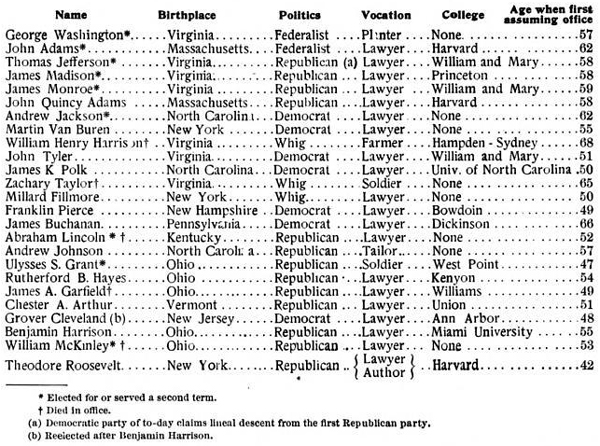

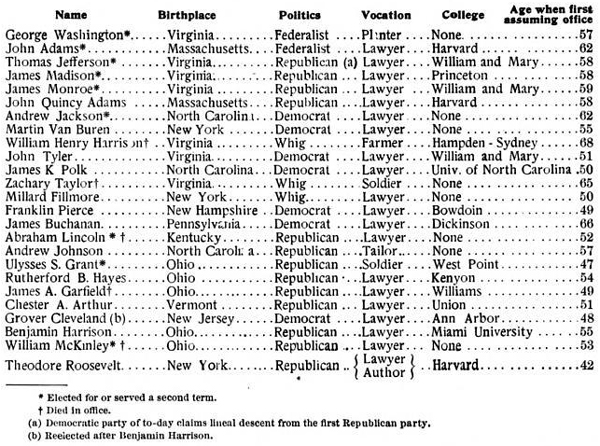

It is interesting and instructive at this time to read again the roll of the presidents of the United States, of whom Theodore Roosevelt is the twenty-fifth. The essential facts are set forth in the following table: [25][26]

Meantime the peoples of the earth have poured

in an avalanche of official and individual expressions of mourning for the dead.

Let one who more powerfully than any other assailed the political policies of

the living McKinley: let Arthur Brisbane, the editor of “The New York Journal,”

tell how the world pays tribute to McKinley fallen:

“It ends to-day.

“Fifty years of struggle and achievement, leading

from obscurity to supreme power and fame, are ‘rounded with a sleep.’

“William McKinley has returned to the home of

his childhood, never to leave it again. The nation stands with bowed head while

the beloved dust is committed to the soil from which it came.

“The abounding activities of American life will

pause this afternoon in a solemn hush.

“The rocket flight of express trains will be arrested

on plain and mountain, the screws of steamships will cease to throb, the tireless

murmur of the bustling trolley will be hushed.

“And, as eighty millions of Americans stand reverently

in spirit by the open grave, all the nations of the earth will stand with them.

“It is the most moving, the most [26][30]

impressive funeral the human race has ever known.

“Never before has a body been committed to the

tomb with so nearly the entire population of the globe as mourners.

“When murdered Caesar was buried, only the people

of a single city knew what was happening.

“When Washington was laid to rest, the toiling

messengers were still galloping over muddy roads with the direful news of his

death.

“The people of the United States were mourners

at the tomb of Lincoln, but there was no cable to bring them into communion

with the sympathetic hearts in Europe.

“But now the whole earth quivers with a single

emotion. A shot was fired in Buffalo, and, as if by an electric impulse, flags

dropped to half mast by the Ganges, the Volga and the Nile.

“The captive Filipino chieftain laid his tribute

of homage upon the tomb of his magnanimous conqueror.

“Boer and Briton joined in sorrow for the distant

ruler who had sympathized with the sufferings of both.

“All the world murmurs to-day: ‘Rest in peace.’

“And the American people—his own people—to whom

he gave his love and his life, echo reverently: ‘Rest.’”

——————————

Testimonies innumerable have been offered to

the manifold good qualities of President McKinley, but it is doubtful if any

has put his finger with more certainty upon the mainspring of the dead man’s

character than has General Charles H. Taylor in his “Boston Globe,” when he

writes:

“Emerson says: ‘If a man wishes friends, he must

be a friend himself.’ William McKinley evidently believed this sentiment, and

carried it out faithfully from the beginning of his life to the end. When thanked

the other day by a man to whom he had been a good friend he simply replied,

‘My friends have been very good to me.’ A man who doesn’t stand by his friends

in religion, in politics, in business and in social life, in adversity and prosperity,

has something lacking in his make-up, which prevents a successful and perfectly

rounded life. President McKinley met this test in a superb and striking manner.

“I have always maintained that any man, no matter

how rich or powerful he may become, no matter what positions of power he may

hold, will, as he draws near the end of his life, find the most satisfaction

in reviewing the acts where he has been helpful and kind to those who are weaker

and poorer than he. President McKinley’s life has been filled with acts of kindness

which made up one of the brightest and most satisfactory pages of his busy life.

He will be sincerely mourned by the American people as a whole, but his memory

will be especially prized by the host of people whose burdens were lifted and

into whose lives rays of sunshine came from the kind heart of William McKinley.”

——————————

The mourners retire, and in the silence of her home the gentle widow bides with bowed head and aching heart. The hearts of her sisters in sorrow yearn to her, their prayers for her are unceasing at the throne of the Almighty God, who alone can solace the afflicted.