|

Affairs at Washington

WHEN I stood in the President’s office at the White House during

the now buoyant, now breathless moments of the last days of our

late beloved President, what a flood of memories came upon me. The

canvas-covered furniture, the cool, white matting, that has replaced

the heavy carpets, the world atlas lying closed on the desk, the

deathly silence and quiet only broken by the ceaseless ticking of

the sounders in the “war telegraph” room—tears came to our eyes

as we looked for the cheery, genial face to complete the picture;

and yet the bulletins at that time were radiant with hope for recovery.

There was the yellow-arm, revolving chair at the head of the table

in the cabinet room, just down the steps. There were the ink well,

pens and calendar just as he had left them when he departed for

the old home in Canton. Captain Loeffler, the veteran doorkeeper,

was still at his post, and all who entered spoke in whispers of

the suffering one. There was a rustle of newspapers in the secretary’s

room, where clippings were being made for the executive mansion

scrap book; adding another chapter to the great portfolio. Outside,

the flowers bloomed with all the mature radiance of autumn.

The White House was being repaired

for the comfort and convenience of the sweet-faced invalid mistress,

on plans made during the happy Maytime. The painters were giving

the portico and railing the finishing touch, and the newly gilded

tops of the railing glistened in the September sunlight. Modest,

home-like, unpretentious, there was a touch of the American devotion

to home-making in it all; an expression of the ruling ideal [5][6]

of the man at the head of the nation, who was first and always for

the fireside and the home circle.

——————————

The heartfelt world-tributes to the

memory of William McKinley have no parallel in all history. A reunited

country—a world’s admiration: from every clime and class—every race

and nation—come the simple tributes of affection, which no words

can transmit; the subtle, inexpressible language of the soul.

Readers of “The National Magazine”

can realize with what a heartache the record must be made—President

McKinley is dead. In common with millions the loss comes to this

writer with the full force of a personal bereavement. What a high

inspiration for the myriads of the human race radiated from the

gentle, unselfish, great heart, that will never cease to beat in

the spirit of love and helpfulness of humankind!

We look up through blinding tears

and listen to the dying words echoing and re-echoing in human hearts

and minds throughout the world:

“It is God’s way. His will, not ours,

be done.”

September 6, 1901, passes into history

as a black and bitter day, lightened only by the sublime courage

and calm resignation of its martyr.

——————————

The personal side of the life of

William McKinley was so perfectly and consistently blended with

his public career, that he was an epoch-making force not alone in

practical affairs, but also in the realm of the spiritual; and his

life and career constitute one of the noblest examples for mankind

in history. [6][7]

There is a tremble in the hand and

a quiver in the voice of whomsoever one meets, in these sad days,

that tells of the death of a martyr president. The endeared wife

and those who gather about the vacant chair at the hearthstone;

every citizen of the great nation; the entire civilized world, aye,

the human race, measures a loss in the death of the brave, gentle

soul that passed away with such words as indicated the dominating

purposes of his life.

It will require years of historical

perspective to measure the full-statured, heroic and triumphant

greatness of William McKinley, a president perfectly blended with

the man as a pure type of Christian manhood; not only mature and

well rounded in itself, but one of those personalities whose simple

strength is a concrete inspiration and influence that will endure

in the lives of millions of American citizens. The close range of

vision makes William McKinley’s life [7][8]

and career a more positive and vitalizing influence upon the young

minds of to-day than even Washington or Lincoln, because William

McKinley is not on a pedestal, lent glamor by the lapse of years,

but was only yesterday a living, breathing presence—a force—coming

into personal touch with this time and this people.

——————————

The world echoes with praise of the

perfect career of William McKinley. He was shot down while extending

that warm, magnetic, helping hand that has done so much for humankind.

The bullet was aimed at the heart that always beat in sympathy for

the wants of his fellow men and idealized the American fireside.

And yet his work was not finished. Such a character was needed to

impress upon human minds the highest and noblest ideals of life;

he was a willing sacrifice to his country—yes, to the human race,

to give the world an ideal sanctified in blood and everlasting love.

——————————

As the President and his wife left

that beloved home in Canton on that bright autumn morning, they

both looked back to view the newly re-painted and re-modeled grey-tinted

home, where they had spent so many happy years; now [8][9]

the repairs were completed, and with all the bright cheerfulness

of bride and groom they talked of “our home.” It was in Canton that

the sweetest and tenderest memories of their life clustered; it

was there that their children were born; and there in sunshine and

shadow, in happiness and sorrow, they had typified the ideal and

sacred devotion of husband and wife.

One lingering look—yes, the last happy

glance homeward for that noble home-maker, who as the gallant, beardless

soldier had won his bride, and kept sacred the altar vows by a life’s

devotion.

The startling crash of window glass

in the Presidential car followed the welcome announcing the arrival

in Buffalo. The presidential salute had come with the shock of an

earthquake; the first thought of the man in whose honor it was given

was for the invalid wife. Tenderly he took her in his arms and his

assurance was enough. With her at his [9][10]

side he was radiant and serenely happy.

“They had more powder than they thought,”

he remarked with a genial smile.

The salutes were fired too close to

the car, and the shattered glass was revealed later as an evil omen

of the shattered hopes of the world, while the people waited for

news from the bedside of the beloved President.

“President’s Day” dawned in the full-orbed

splendor of Autumn. The air was rich with the fragrance of full

fruitage. The golden month was at her best. “It’s McKinley weather”

was on every lip as a hundred thousand people started on their way

to the Pan-American Exposition grounds to see “our President.” Early

in the morning the distinguished guests at the Milburn house on

Delaware street were astir. The President carried the copy of his

speech in his inside pocket and stopped during his brief morning

walk about the grounds to jot down a new word or idea.

“I never have overcome the nervousness

that comes over me before making a speech,” he jocularly remarked,

adjusting his glasses. That speech was the ripe thought of the greatest

American statesman of the times—and is one that will live in history.

It was the summarizing of an epoch in national destiny, while the

swift-moving events which it recorded were still fresh in the minds

of the people. It was an account of his stewardship to the American

nation, fraught with inspired foresight and fragrant with love and

affection for the people and the highest ideals of patriotism.

——————————

The carriage bore them through the

crowds to the Triumphal Bridge and then in the full glory of the

September morning, with the gay flutter of flags of all America

and the dreamy haze of Indian summer settling over the esplanade

and fountains, the people gathered to hear what was destined to

be the farewell address of the twenty-fourth president of the United

States. There was a hush when he arose to speak, and the deliberation

with which he wiped his eye glasses gave him time to overcome the

nervousness that confronted him at the opening of every address.

Raising his head and looking over his glasses in a kindly way, in

full, rounded, measured tones, he delivered an address which was

caught up and flashed around the world within a few hours of its

utterance. It was an important message to the world and looked to

the future. How gentle and significant was the scene; for nowhere

have the peaceful achievements of the country been more thoroughly

indexed than at the Pan-American. The throng that assembled on that

bridge was an interesting study—truly typical of the country.

——————————

Citizens from all the various states

and territories brushed elbows there; diplomats from the nations

of the world, silk-tiled [sic] and conventional in black

Prince Alberts. Orient and Occident were merged in that throng and

everyone was thrilled. Thousands stood by patiently until the last

words were spoken, although comparatively few in that vast assembly

could hear what the speaker said. Little did any one think what

precious, golden moments were passing!

——————————

Conspicuous in the crowd assembled

on the Esplanade to hear President McKinley’s speech, were several

“National Magazine” badges, worn by delegates to the “National’s”

Pan-American Convention who remained to greet the President. He

sent his regrets at being un- [sic] to attend the “National’s” convention.

Children were everywhere present, and gave vent to wilder enthusiasm

than their elders. A pretty little maiden with fluffy hair demurely

stood in her father’s coat pocket, with her arms tightly clasping

his neck, and from this exalted posi- [10][12]

tion she was the first of her little group to see the President

as he drove up.

“See! there he is! mamma, papa, mamma,

there he is! Get up here, mamma; you can see just fine!”

The good natured crowd laughed at

the childish enthusiasm.

“I want to see,” came a pleading voice

from a little boy who was digging his head in the coat tails of

a man in front. A second later he was elevated to the broad shoulders

of a six-foot giant and a tired little woman murmured a word of

thanks to the stranger.

“Down with the boy!” shouted a man

just behind, who was short in stature.

“Never!” came back the reply. “You

can’t down the American boy.” And the short man cheered with the

rest.

“Mamma, did you see? He wipes his

glasses just like Uncle George. Oh, but he must be a nice man.”

“Hush, my child,” said the father, but the seed had been sown for

a new thought in the mind of a grey-haired man standing near.

“That’s just the way Lincoln used

to do. It’s the same thing over again; our greatest presidents are

the humblest.”

——————————

The party was driven to the Stadium.

The presence of carriages on the grounds was a mark of the distinguished

occasion. And yet do you know one of the ambassadors remarked that

it was suggestive of a funeral cortege. The President preferred

walking among the people, where it was possible.

Very sturdily he walked into the great

Stadium under a scorching sun, to review the troops. The great,

umbrella-bearing throngs rose to greet the President as he passed,

and every [12][13] outburst of applause

was met with that graceful bow and sincere salute which was distinctly

characteristic of William McKinley. It was an expression of patriotic

and personal devotion seldom witnessed. Standing on the reviewing

stand I was thrilled to the finger tips, and somehow the thought

flashed over me: Is this the crest of the wave?

His last review will remain a vivid

memory to the thousands in the arena. As the troops passed with

that elastic, swaying quick step, keeping time to Sousa’s new march,

the “Invincible Eagle,” the President’s face beamed his pleasure

and his coat was flying open as if showing the open hearted honesty

of the man; he was somehow a part and parcel of the people, and

it was the people who furnished the pageant for him rather than

the troops. The diplomatic corps, representing all nations, caught

the infectious enthusiasm and one member remarked:

“Such patriotism is an invulnerable

bulwark of national strength.”

As the late President ascended the

steps of the stand, gravely dignified but happy-faced, his deep

blue eyes glistened in the radiant noon-day sun. He graciously bowed

to the ladies on the stand.

“Are you fatigued,” inquired a lady

standing near me.

“Oh, no; I’ve had a good six weeks’

rest at home,” he replied in his cheery way.

As he turned to watch the troops,

with the fingers of one hand he tapped the railing in time with

the music, for if any one liked music it was our late President.

Alert, attentive and always interested, he made every man in line

feel that he was receiving personal greeting. And herein was one

secret of the superlative strength of William McKinley; he was always

interested, and his sincerity was never questioned, nor was there

ever a partiality. Always poised for emergencies, never did a shadow

of hypocrisy pass over that kindly face. When he turned and saw

my “National Magazine” convention badge of red, white and blue,

he smiled.

“The colors are right”—and then, al-

[13][14] most in the same breath, were

scattered those brief words and acts of kindliness to scores of

others which enshrine his memory in affectionate remembrance.

As the party passed out near the court

of lilies, the homing pigeons were brought forth from the dove-cote

and long and steadfastly he gazed at the circling birds, emblematic

of the peace he loved. Peace, prosperity and happy homes were the

watchwords of his career, from the time when he first took an official

green bag as county attorney, until the last days of his life.

——————————

That evening, in the gentle twilight

of fairyland glowing on the shore of Mirror lake, with the illuminated

buildings and trees in the background, the President witnessed for

the last time the glories of nocturnal splendor. Happy and cheerful,

and as interested as when a barefoot boy at Niles, Ohio, when the

Fourth of July pyrotechnics were in progress, he enjoyed every flash

of the swift, shooting rockets and clusters of light in the cloud-banked

sky. The flickering shadows and the dense darkness among the trees

made some of his personal protectors tremble, but he seemed to have

no consciousness of peril and discussed lightly the plan for the

morrow, when he was to visit Niagara.

Ah, that most touching, last morning!

From the vine-covered verandah he came, with Mrs. McKinley, to greet

the splendor of the new day! With her coat on his arm, (no man was

ever more devoted) he turned to greet even those who held the cameras.

The grand old flag he loved made the background of the picture.

Mrs. McKinley was hidden behind a parasol, and even there was the

genial face of the President to say:

“I’ll just have to let you have a

picture.”

What a happy day seemed ahead! Appreciative

of every moment the President and members of the cabinet stood upon

the banks of the greatest wonder of the world, and watched the water

in its onward rush to the sea. Thoughtful and considerate of the

comfort of his wife and others, he had never a care for his own

pleasure.

——————————

Just three hours before the fatal

shot was fired, the President, for the first time in weeks, requested

a picture. Quick as a flash it was taken by Mr. Dunn of “Leslie’s

Weekly,” before the word was scarcely uttered. Attired simply in

a silk hat and black Prince Albert, with a white vest, from which

hung a simple gold fob, and his gloves, he looked every inch the

great man he was.

The President’s watch came out frequently,

because if there was ever a methodical, punctual man, he was, and

most anxious that the thousands at the Temple of Music should not

be kept waiting. The train arrived at the north gate and the party

was hurried past the Propylea [sic] and well into the midst

of a sea of humanity, greeting him as he proceeded.

He wore an air of serious purpose,

as he pressed onward, not to disappoint or keep the people waiting.

The throng were packed against the door and had to pass in and out

through an improvised aisle lined on either side with seats. Directly

between the two stood the President, with Secretary Cortelyou on

the right and President Milburn on the left. The President pulled

out his watch again to see if he was on time, and looked about admiring

the interior of the temple. Little could I think, as I caught a

last glimpse of that beloved face among the hustling crowd, of the

impending tragedy. Here in the gaieties of dedication day songs

and chimes had gone forth; the Vice-President and Senator Lodge

had spoken with Senator Hanna on the platform. Here, during the

summer days, music lovers had gathered at the recitals given at

this now fatal hour of four o’clock every afternoon. Here it was

our Frederick Archer’s magic touch had [14][16]

brought forth the heights and depths of the “Pilgrim Chorus” from

“Tannhauser.” Here it was that the very artistic spirit of the Exposition

centred—in fact—the magnet, the meeting point, the place where the

sessions of all of the conventions and all special day exercises

had been held. Here was where romance, comedy, music dwelt—and now

deep-dyed tragedy stalked in.

——————————

The people began to pass forward,

shake the President’s hand and move on. In the twinkling of an eye

it occurred. Standing within fifty feet were hundreds of people

who did not know what had taken place. There were two shots in quick

succession, about 4:12 p. m., but nothing was thought of that because

it could easily be confounded with the shooting from Indian festivities

outside. I saw vaguely a scuffle and my thought was, “Some drunken

man.” Then, when the President was taken to the inner side of the

stage my first thought was that he had fainted from the fatigue

of the arduous duties of the day. The people were stunned when the

first ghastly whisper came across the room:

“The President is shot!”

Many would not believe it, but a few

moments later, when they carried a limp form out to the ambulance,

with the crimson blood staining the white vest, the awful realization

came. Men, women and children burst into tears, the hard, white

lines showed first in a desire to mete out some adequate punishment

to the cowardly assassin.

The frenzy was fearful to contemplate.

“String him up! Kill him!”

Czolgozc—Shawlgotch—the young Polish-descended,

American-born Anarchist, was beaten down by soldiers and the Georgia

negro waiter at the Plaza restaurant, who was in line, and before

the dazed crowd had realized the truth, the officers tried to sooth

[sic] them with the report that it was all a mistake; but

very soon all knew that the President was lying in the Pan-American

Emergency Hospital, wounded and near to death.

——————————

The deadly hurts were tended with

all the skill that the President’s own physician, Dr. Rixey, and

a group of famous colleagues could bring to bear, and the distinguished

patient was removed to the Milburn house, where his stricken but

brave wife might be near him in any crisis that might impend.

“This is not our first battle, Ida,”

he [16][17] said to the sobbing woman

at his bedside. “We have won more desperate cases than this. And

though conditions may be critical, if there were only one chance

in a thousand I would accept that chance and, for your sake, hope

to win.” Then followed the days of hopeful news from that bedside,

when it seemed as if the indomitable courage of the wounded man

would conquer, and he would be spared to his people. The public

fears grew lighter as reassuring bulletins followed each other twice

or thrice daily.

What a wave of grief, almost of anguish,

swept over the land when on Friday morning, September 13, just a

week after the shooting, the correspondents camped in tents across

the street from the Milburn home flashed to all the world the word

that the President had had a relapse—that he was very low, sinking,

and that the doctors had all but yielded the last hope. The world

stood still with bated breath, praying, hoping against hope that

he might rally and rise from the dark shadows that encompassed him.

But it was not to be. Recovering consciousness

near the last, the dying man bade his physicians to cease the futile

struggle. “Let me die,” he whispered. He knew that he must go, and

with the simple, sublime courage that marked him on the field of

Antietam, he met the inevitable with calm and unruffled front.

——————————

In this interval of consciousness

Mrs. McKinley was brought into the death chamber. The President

had asked to see her. She came and sat beside him, held his hand,

and heard from him his last words of encouragement and comfort.

Then she was led away, and not again during his living hours did

she see him.

The President fully realized that

his [17][18] hour had come and his

mind turned to his Maker. He whispered feebly: “Nearer, My God,

to Thee,” the words of the hymn always dear to his heart. Then in

faint accents he murmured:

“Goodbye, all; goodbye. It is God’s

way. His will, not ours, be done.”

With this utterance the President

lapsed into unconsciousness. He had even then entered the valley

of the shadow.

Slowly the hours passed without visible

change in his condition, but there was no more hope. There was only

the tense waiting for that moment when the great soul should quit

its house of clay. At two o’clock in the morning of Saturday, September

14, Doctor Rixey was the only physician in the death chamber. The

others were in an adjoining room, while the relatives, cabinet officers

and near friends were gathered in silent groups in the apartments

below. As he watched and waited, Dr. Rixey observed a slight, convulsive

tremor run through the President’s frame. Word was at once taken

to the immediate relatives, who were not present, to hasten for

the last look upon the President in life. They came in groups, the

women weeping and the men bowed and sobbing.

——————————

Grouped about the bedside at this

final moment were the only brother of the President, Abner McKinley,

and his wife; Miss Helen McKinley and Mrs. Sara Duncan, sisters

of the President; Miss Mary Barber, niece; Miss Sara Duncan, niece;

Lieutenant James F. McKinley, William M. Duncan and John Barber,

nephews; F. M. Osborne, a cousin; Secretary George B. Cortelyou,

Charles G. Dawes, controller of the currency; Colonel Webb C. Hayes

and Colonel William C. Brown.

With these, directly and indirectly

connected with the family, were those others who had kept ceasless

[sic] vigil—white-garbed nurses and the uniformed Marine

Hospital attendants. In an adjoining room were Drs. Charles Burney,

Eugene Wasdin, Roswell Park, Charles G. Stockton and Herman Mynter.

The minutes were now flying, and it

was 2:15 a. m. Silent and motionless, the circle of loving friends

stood about the bedside.

Dr. Rixey leaned forward and placed

his ear close to the breast of the expiring President. Then he straightened

up and made an effort to speak.

“The President is dead,” he said.

The President had passed away peacefully,

without the convulsive struggle of death. It was as if he had fallen

asleep. As they gazed on the face of the dead, only the sobs of

the mourners broke the silence of the chamber of death.

——————————

The last honors paid the dead chieftain

in Buffalo, in Washington and in his home city of Canton are still

too fresh in the public mind to require full recital. Let it be

recorded, however, that not one of the many and mighty triumphs

of McKinley’s life approached in scope or intensity his last great

triumph won in death. Such an outpouring of love and devotion was

never paid to the memory of any man in all the history of the earth.

There was scarcely a dry eye among the scores of thousands that

looked upon the nation’s dead where he lay in funeral state, at

Buffalo, at Washington and at Canton. In proudest palace and in

humblest cot and tenement alike the sorrow of his people was profound.

Men who had fought him hardest in life paid tear-wet tributes to

his goodness, his loyalty to his country and his God. Never a man

to evoke bitterness against himself, in this hour of his passing

he compelled, by the sweetness and purity of his career, the unreserved

love of all them that had opposed him.

The hand that sought to strike him

down did but exalt him. It served but to throw into a stronger light

those mag- [18][20] nificent qualities

that made him the best and most universally beloved chief magistrate

that America ever had.

——————————

One incident of the state funeral

at Washington was perhaps more beautifully illuminative of the ties

between McKinley and his people than any other memory of that sad

occasion. At the start of the procession up Pennsylvania avenue,

Monday evening, one wavering soprano voice back somewhere in the

wilderness of people sang “Nearer My God To Thee,” the notes of

which were on the lips of the President as he descended slowly into

the valley of the shadow of death. The affecting refrain was caught

up by thousands of subdued voices, which carried it up the thoroughfare,

keeping pace with the cortege till the hymn burst forth from thousands

more who were banked in upon Lafayette square opposite the White

House gates, making the heart swell and tears to gush from eyes

that watched the progress up the circular drive under the port cochere.

No wonder that later on Monday night Senator Louis McComas, of Maryland,

standing on the curb near the temporary residence of the new president,

remarked: “The sublime faith in which William McKinley died has

done more for the Christian religion than a thousand sermons preached

in a thousands [sic] pulpits on a thousand Sundays.”

——————————

The funeral train, bearing the remains

of the beloved President from Buffalo to Washington, and from Washington

to the loved home in Canton, awakened an expression of national

sentiment that has no comparison. The unanimous personal sympathy

of the people, enduring privation and hardship in order to offer

an individual tribute to the memory of the dead, was not adequately

recognized in the newspaper accounts. The bells tolled, the people

watched and waited in storm and darkness for hours, and all hearts

echoed one continuous refrain of their fallen leader’s favorite

hymns—“Nearer, My God, to Thee,” and “Lead, Kindly Light.” The telegraph

wires were laden with eloquent descriptive stories inspired by the

scenes en route to the state funeral at Washington, from the first

trying ordeal at Buffalo, when President Roosevelt and the cabinet

and the endeared friends looked upon the thin, placid face at the

Milburn home, where the first simple services were held.

How fitting that the final tribute

to the remains should be paid at the old home he loved so well;

there among the scenes where the sweetest and tenderest memories

of his life clustered. I never expect to witness again more impressive

scenes. The hands of the city clock were stopped at 2:15, the hour

of his death, and through the court house passed thousands of old

friends from surrounding towns to look upon the face of one they

loved until the pale glare of the electric light lit up the mourning

draped walls. A soldier and a sailor of the United States stood

at the head and foot of the casket draped with the flag which had

waved so victoriously at the time of his first nomination for the

presidency.

What a contrast with the thrilling

scenes of ’96, when the crowds came to do honor to the living, with

huzzas [sic]—now hushed and silent. The modest little home,

which I had visited a few weeks ago, and the new porch, which had

been so proudly pointed out by the President, carried no semblance

of mourning. An additional electric arc light glowed at the side

of the house. The throngs passed noiselessly and with bare heads

as the soldier sentinel paced the lawn, trampled by enthusiastic

admirers only a few years before. The shutters were closed and thousands

kept watch on the last night that this little home contained the

mortal remains of the dead President. The flowers in urn and vase

shimmered with the September [20][22]

dew, as if they, too, were experiencing a grief at the loss. Most

pathetic was the sight of the empty willow rocker, where he sat

so many times, swaying back and forth in the pleasant autumn evenings.

What a pathos in this home scene, and what a flood of recollections

it awakened!—the summer Sabbath evenings on the porch when they

returned from Washington, and the little girl played on the violin

“Home, Sweet Home” and “Nearer, My God to Thee;” the cheery sight

of the President taking his fair wife to drive, as gallant as a

lover; the swinging walk up and down Market street, to and from

a well-ordered and busy law office.

William McKinley came to Canton at

the suggestion of a beloved sister, who taught in the public schools,

who was an inspiration of his life, and who now sleeps in the cemetery

where her distinguished brother rests in peace. Here was the stone

church where the young lawyer had taken the vows which were sanctified

by a life’s devotion as a husband. And on another corner was the

church in which he worshipped. In the fourth pew from the front,

No. 10 in the centre aisle, was where he sat and loved to sing in

full, round bass those dear old Methodist hymns which have cheered

the souls of countless millions. Every scene in this busy little

city he loved seemed in some way associated with him. I arrived

by way of Massilon; the dusty road was fringed with vehicles bringing

the people. Special trains from all directions poured in until it

seemed as if there could not possibly be room for any more. The

telephone and trolley poles were draped and there was not a house

or habitation that was not in mourning.

The floral tributes have probably

never been equalled. From every nation, from almost every organization,

came these tributes—expressing much and eloquent sympathy in the

language of heaven. And yet, with all this expression of a world’s

admiration and affection, the love of the old friends and neighbors

was the most impressive after all.

——————————

Vice-President Roosevelt, reassured

by the hopeful bulletins sent out by the President’s physicians

during the first week, and having not the least doubt of the President’s

speedy recovery, had gone into the northern New York woods to hunt.

There the news of his chief’s demise

reached him. As rapidly as special trains could bear him on he rushed

to Buffalo, where the members of the cabinet were assembled. He

went at once to the home of his friend, Ainsley Wilcox, and at 3:39

o’clock on the afternoon of Saturday, September 14, he took the

oath of office as President of the United States.

The scene, as witnessed and described

by a staff writer of “The Boston Globe,” was one of the most dramatic

and awesome in American history, and will never be forgotten by

the half hundred persons who witnessed it.

The officials arranged themselves

in a semi-circle, the Vice-President in the centre.

On his right stood Secretaries Long

and Hitchcock, and the Vice-President’s private secretary, William

Loeb. Standing on his left were Secretaries Root, Smith, Wilson

and Cortelyou and Senator Depew. About the room were scattered Ansley

Wilcox, James G. Milburn, Doctors Mann and Mynter, physicians to

the late President; Dr. Charles Carey, William Jeffords, official

telegrapher of the United States Senate; Colonel Bingham of Washington,

the newspaper men and several women friends and neighbors of the

Wilcox family.

At precisely 3:32 o’clock Secretary

Root said in an almost inaudible voice:

“Mr. Vice President, I—” then his

voice broke, and for fully two minutes the tears ran down his face

and his lips [22][24] quivered so that

he could not continue his utterances.

There were sympathetic tears from

those about him, and two great tear drops ran down either cheek

of the successor of William McKinley.

Mr. Root’s chin was on his breast.

Suddenly throwing back his head as if with an effort, he continued

in a broken voice:

“I have been requested on behalf of

the cabinet of the late President—at least those who are present

in Buffalo, all except two—to ask that for reasons of weight affecting

the affairs of government you should proceed to take the constitutional

oath of office of the President of the United States.”

——————————

Judge Hazel had stepped to the rear

of Mr. Roosevelt, and the latter coming closer to Secretary Root,

said in a voice that at first wavered, but finally became deep and

strong, while as if to control his nervousness he held firmly the

lapel of his coat with his right hand:

“I shall take the oath at once, in

accordance with your requests, and in this hour of deep and terrible

national bereavement I wish to state that it shall be my aim to

continue, absolutely unbroken, the policy of President McKinley,

for the peace and prosperity and honor of our beloved country.”

——————————

Mr. Roosevelt stepped farther into

the bay window, and Judge Hazel, taking up the constitutional oath

of office, which had been prepared on parchment, asked Mr. Roosevelt

to raise his right hand and repeat it after him.

There was a hush like death in the

room as the judge read a few words at a time and the President in

a strong voice and without a tremor and with his raised hand as

steady as if carved from marble repeated it after him.

“And thus I swear,” he ended it. The

hand dropped by his side, the chin for an instant rested on the

breast and the silence remained unbroken for a couple of minutes,

as though the new President of the United States were offering silent

prayer.

Judge Hazel broke it, saying: “Mr.

President, please attach your signature.”

And the President, turning to a small

table near by, wrote “Theodore Roosevelt” at the bottom of the document

in a firm hand and at 3:39 o’clock Theodore Roosevelt began his

career as President of the United States at the age of forty-two.

Secretary Root was the first to congratulate

him. The President then passed around the room and shook hands with

everybody.

The first act of the new President,

his formal announcement calculated to reassure the industrial interests

of the country, won the confidence of these great interests, and

the toilers dependent upon them, and made it sure that the tragedy

which had shocked the world would not be followed by the depressing

effect of administrative uncertainty. The new President’s first

official act was to proclaim the following Thursday, September 19,

as a day of mourning and prayer throughout the United States. In

this proclamation he said:

“A terrible bereavement has befallen

our people. The President of the United States has been struck down;

a crime committed not only against the chief magistrate, but against

every law-abiding and liberty-loving citizen.

“President McKinley crowned a life

of largest love for his fellow-men, of most earnest endeavor for

their welfare, by a death of Christian fortitude; and both the way

in which he lived his life and the way in which, in the supreme

hour of trial, he met his death, will remain forever a precious

heritage of our people.

“It is meet that we as a nation express

our abiding love and reverence for his [24][25]

life, our deep sorrow for his untimely death.

“Now, therefore, I, Theodore Roosevelt,

President of the United States of America, do appoint Thursday next,

September nineteen, the day in which the body of the dead President

will be laid in its last earthly resting place, as a day of mourning

and prayer throughout the United States.

“I earnestly recommend all the people

to assemble on that day in their respective places of divine worship,

there to bow down in submission to the will of Almighty God, and

to pay out of full hearts their homage of love and reverence to

the great and good President whose death has smitten the nation

with bitter grief.”

——————————

Theodore Roosevelt, as stated elsewhere,

is the youngest man ever called to the presidency of the United

States. But he is remarkably well equipped by an unusual training

to fulfill the vast and innumerable duties of that position. His

career has been an open book to his fellow-citizens for many years

past; as author, soldier and public servant he has been always essentially

a vigorous, forceful, high-minded man—a natural leader. He aspired

to the presidency, and there were very many men high in the councils

of his party who regarded him as the logical successor of President

McKinley in 1905. Now that the decree of Providence has called him

to that succession, the great majority of his fellow-citizens share

the conviction expressed by United States Senator Thomas C. Platt

of New York, that “he will be a great President.” He has given the

clearest evidence of wise statesmanship by pledging all the members

of President McKinley’s cabinet to serve out their terms as if there

had been no change in the head of the administration. It is conceeded

[sic] that Mr. McKinley, with his genius for executive affairs,

drew about him one of the ablest and best balanced cabinets that

has ever sat in Washington.

——————————

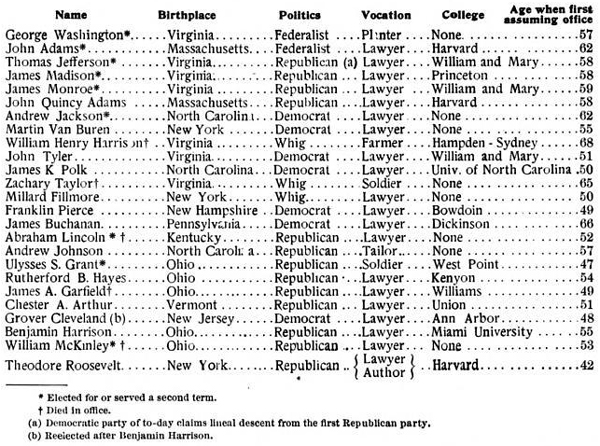

It is interesting and instructive

at this time to read again the roll of the presidents of the United

States, of whom Theodore Roosevelt is the twenty-fifth. The essential

facts are set forth in the following table: [25][26]

Meantime the peoples of the earth

have poured in an avalanche of official and individual expressions

of mourning for the dead. Let one who more powerfully than any other

assailed the political policies of the living McKinley: let Arthur

Brisbane, the editor of “The New York Journal,” tell how the world

pays tribute to McKinley fallen:

“It ends to-day.

“Fifty years of struggle and achievement,

leading from obscurity to supreme power and fame, are ‘rounded with

a sleep.’

“William McKinley has returned to

the home of his childhood, never to leave it again. The nation stands

with bowed head while the beloved dust is committed to the soil

from which it came.

“The abounding activities of American

life will pause this afternoon in a solemn hush.

“The rocket flight of express trains

will be arrested on plain and mountain, the screws of steamships

will cease to throb, the tireless murmur of the bustling trolley

will be hushed.

“And, as eighty millions of Americans

stand reverently in spirit by the open grave, all the nations of

the earth will stand with them.

“It is the most moving, the most [26][30]

impressive funeral the human race has ever known.

“Never before has a body been committed

to the tomb with so nearly the entire population of the globe as

mourners.

“When murdered Caesar was buried,

only the people of a single city knew what was happening.

“When Washington was laid to rest,

the toiling messengers were still galloping over muddy roads with

the direful news of his death.

“The people of the United States were

mourners at the tomb of Lincoln, but there was no cable to bring

them into communion with the sympathetic hearts in Europe.

“But now the whole earth quivers with

a single emotion. A shot was fired in Buffalo, and, as if by an

electric impulse, flags dropped to half mast by the Ganges, the

Volga and the Nile.

“The captive Filipino chieftain laid

his tribute of homage upon the tomb of his magnanimous conqueror.

“Boer and Briton joined in sorrow

for the distant ruler who had sympathized with the sufferings of

both.

“All the world murmurs to-day: ‘Rest

in peace.’

“And the American people—his own people—to

whom he gave his love and his life, echo reverently: ‘Rest.’”

——————————

Testimonies innumerable have been

offered to the manifold good qualities of President McKinley, but

it is doubtful if any has put his finger with more certainty upon

the mainspring of the dead man’s character than has General Charles

H. Taylor in his “Boston Globe,” when he writes:

“Emerson says: ‘If a man wishes friends,

he must be a friend himself.’ William McKinley evidently believed

this sentiment, and carried it out faithfully from the beginning

of his life to the end. When thanked the other day by a man to whom

he had been a good friend he simply replied, ‘My friends have been

very good to me.’ A man who doesn’t stand by his friends in religion,

in politics, in business and in social life, in adversity and prosperity,

has something lacking in his make-up, which prevents a successful

and perfectly rounded life. President McKinley met this test in

a superb and striking manner.

“I have always maintained that any

man, no matter how rich or powerful he may become, no matter what

positions of power he may hold, will, as he draws near the end of

his life, find the most satisfaction in reviewing the acts where

he has been helpful and kind to those who are weaker and poorer

than he. President McKinley’s life has been filled with acts of

kindness which made up one of the brightest and most satisfactory

pages of his busy life. He will be sincerely mourned by the American

people as a whole, but his memory will be especially prized by the

host of people whose burdens were lifted and into whose lives rays

of sunshine came from the kind heart of William McKinley.”

——————————

The mourners retire, and in the silence

of her home the gentle widow bides with bowed head and aching heart.

The hearts of her sisters in sorrow yearn to her, their prayers

for her are unceasing at the throne of the Almighty God, who alone

can solace the afflicted.

|

![]()